How Mining Waste and Microwave Technology Could Solve the Rare Earth Shortage

ChE/COS Assistant Professor Damilola Daramola developed a method using chemical treatments and microwave reactors to extract rare earth elements from coal tailings two to three times more efficiently than standard approaches.

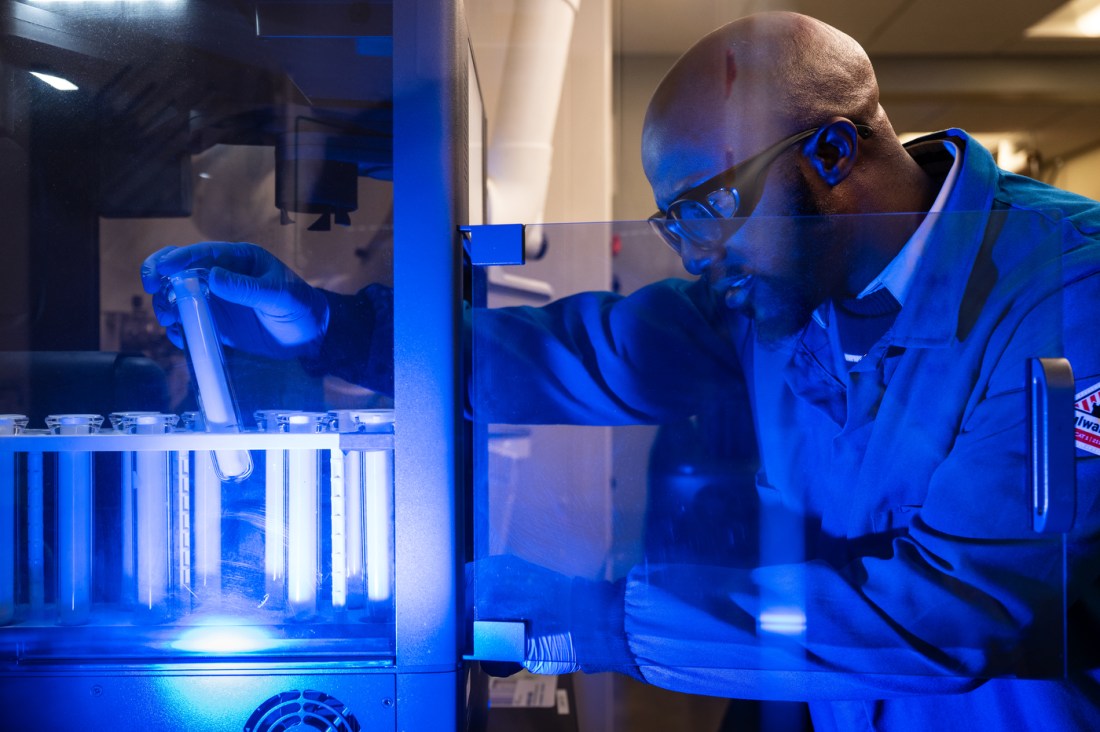

This article originally appeared on Northeastern Global News. It was published by Noah Lloyd. Main photo: Extracting rare earth elements, used in many technologies, is a difficult job. Coal tailings, the mining byproduct shown here, offer a solution. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

How coal tailings could help solve the United States’ need for rare earth elements

New Northeastern research has identified a method of extracting rare earth elements from the mining waste product that is two to three times more efficient than previous approaches.

Rare earth elements are an easy-to-find, hard-to-refine resource critical for everything from magnets and electronics to batteries and catalysts for chemical reactions. Since the 1980s, a race has been on between the United States and China for dominance of the rare earth element market — and the United States is losing.

New research out of Northeastern University has discovered a new way to extract rare earth elements out of coal tailings, the cast-off soil and rock left behind by coal mining. Using a chemical treatment and a specially designed microwave reactor to control the temperature, the researchers have doubled the extraction levels previously possible.

How rare are rare earths?

Rare earth elements, often just called rare earths, aren’t really all that rare, according to the Science History Institute. Rather, in nature, they appear mixed with other elements, sometimes radioactive ones, making them difficult to refine.

Damilola Daramola, an assistant professor in the departments of chemistry and chemical biology, and chemical engineering at Northeastern, says rare earth elements are often made accessible as byproducts of other mining operations. For his purposes, that means coal.

|

|

Damilola Daramola used a chemical solution and specialized microwave reactor on samples of coal tailings to extract rare earths. He and his research team discovered that their method was twice as effective as conventional approaches. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Burning the carbon in coal leaves behind an ash of inorganic compounds, often called fly ash, which Daramola says has been well-studied for rare earths. But coal tailings, the mountains of unwanted detritus left behind by coal mining, remain an underused resource, partly due to the ready availability of fly ash and partly due to the fact that there is simply all that organic material still left to sift through in the tailings, he continues.

By pretreating the coal tailings in a solution of water and sodium hydroxide, or lye, and then bathing them in nitric acid while controlling the temperature of the reaction through a specialized microwave reactor, Daramola and his team found that they could extract rare earths two to three times more efficiently than in the standard methods used on coal byproducts.

“That combination, of being able to thermally stimulate the material,” alongside the treatment with sodium hydroxide, Daramola says, “well, it turns out that what you’re doing is actually changing the solid structure of this material” and allowing for the extraction of valuable rare earths.

Daramola and Northeastern Ph.D. student Lawrence Ajayi, the first author of the study, say that the rare earths they extracted have a diverse range of applications. Neodymium, Ajayi gives as one example, is “the third-most abundant element in the tailings, and it happens, also, to be very important for energy,” being found in high-powered magnets and the motors for both electric vehicles and wind turbines.

|

|

Lawrence Ajayi, a Northeastern Ph.D. student and the first author on the paper, says that “we have so many abandoned mines that we could take advantage of” in the United States. The global rare earths market is currently dominated by China, but the billions of tons of tailings scattered around the U.S. could prove to be a hidden resource. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Read full story at Northeastern Global News