Dainty flower is relentless cancer killer in disguise

When I was in high school I read a book called Tales of a Shaman’s Apprentice that I thought was going to define the rest of my life (I’ve always been kind of dramatic like that). It was about discovering the chemical compounds found in plants that cultures have been using for centuries, even millennia, to treat disease. I was convinced I’d found my calling: I would hike through rainforests with indigenous medical experts collecting delicate specimens to bring back to the lab and study. Actually, a not-so-small part of me still thinks this sounds pretty much amazing.

The book and the dream came flooding back to me recently when I met chemical engineering professor Carolyn Lee-Parsons, Northeastern’s resident expert on the Madagascar Periwinkle. This dainty little flower may look like your average garden plant, but lurking behind an unassuming disguise of pink petals and pretty leaves lies an important pharmaceutical production facility that has been supplying the people of Madagascar and much of the tropics with treatments for various diseases for centuries.

In the mid-twentieth century, two of the compounds produced in its sap were identified as superb anti-cancer drugs. Vinblastine and vincristine are alkaloids, or basic compounds, that halt the production of tubulin, which is like the skeleton of a cell. “It’s really like a chemical arsenal that they unleash to kill bacteria, fungus, insects,” explained Lee-Parsons. The only problem with the business plan that exploits this native arsenal, is that the products are extremely expensive.

The commercial drug that contains naturally harvested vinblastine costs $2 million per kilogram, while the one containing vincristine costs $15 million per kilogram. Each drug-producing cell in the periwinkle plant contains but a tiny fraction of the anti-cancer drug: 0.0005 percent of the cell’s dry weight. It’s also very difficult to control the production of the plants: things like sunlight, infectious bacteria and seasonality make farming a less than ideal model for pharmaceutical drug production.

But Lee-Parsons is taking advantage of an interesting quirk of life to increase the percentage of drug produced by the plant cells. Just like the human body, where different organs have different specialties and thus produce different cell-types, the leaves, roots and shoots of the Madagascar Periwinkle each has its own particular job within the organism. “By understanding the plant biology,” she explained, “we can take any part of the plant and by applying special plant hormones we can direct its development.”

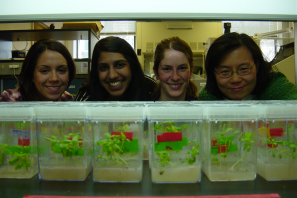

Her team grows little flasks full of leaves or roots or even just cell suspensions–which she said look something like green applesauce. In the wild, of course, none of these would survive since they all rely on each other. The leaves do photosynthesis to secure oxygen for the whole system. The roots suck up nutrients and water from the ground. Without leaves, and thus without oxygen, the roots are pretty destitute. In the lab, where Lee-Parsons’ team is like a band of busy nurses, all working to keep these starving foundlings alive. They provide special growth media that allow the various cell-cultures to thrive, even in the absence of their compatriot plant parts.

Now that the cells are being expertly cared for, they no longer have to worry about keeping themselves alive. Now, when Lee-Parsons applies certain hormones to spark the production of drug-producing cells, they can actually devote some resources to that job.

I’m not a big gardener. I tend to forget that basic things like water and sun are required to keep my houseplants alive, so when they start dying I wonder why (an early cue that my career as a shaman’s apprentice was unlikely). But my fiance is and he recently educated me on the fact that if you cut off the flower heads of herb plants, they will be able to devote more resources to making leaves. They would really rather reproduce so after a while they start sending out seed-containing flowers but we, wanting tasty salad dressings and such, nip that process in the bud. Literally. This is similar to what Lee-Parsons is doing in the lab. She allows the plant cells to focus on a single job — drug production — without having to worry about all the other things that go into survival in the standard environment.

By combining the knowledge of various types of experts, from biologists to analytical chemists to geneticists, Lee-Parsons engineers systems that can produce pharmaceutical products in much greater abundance than the plants naturally do on their own. If she can bring the concentration up by even a fraction of a percent, she could help to significantly reduce the cost of the drugs.